On Friday evening last week, we had a remarkable moment of technological globalization in my Accra home–what students who have taken my Globalization class at UW Bothell might recognize as an example of time-space compression. I was sitting upstairs here at my desk, speaking on the phone to Joe Weisenthal at Bloomberg Television in New York. Downstairs, my partner was watching the program “What’d You Miss?” on Bloomberg, and listening to me speak on the segment, “What’s behind the surge in cocoa prices?” The sound signals of the conversation between me and Joe bounced back and forth between Ghana and the US, and when they arrived on our television screen here, they were accompanied by images of me, my new book, Cocoa, price graphics, farms, and factories.

I decided to extend the information loop once again and write a post recapping my explanation of cocoa’s recent price rise for “What’d You Miss?”, and give an update on what’s happened between Friday and today. In just a few days, there is more to add to the story.

When I was putting the final touches on my Cocoa manuscript last year, the ICCO Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics forecast a surplus for the 2016-17 cocoa season, which turned out to be correct. To understand why we had a surplus (which means that the total amount of cocoa grown that season was more than was needed for grindings during the same period), we need to look back at what was happening the year before.

About halfway through 2016, an El Niño cycle came to an end. El Niño cycles alternate with La Niña cycles; El Niño is the “warm” cycle and La Niña is the “cool” cycle. As climate change makes El Niño cycles harsher, that translates into drought conditions here in West Africa.

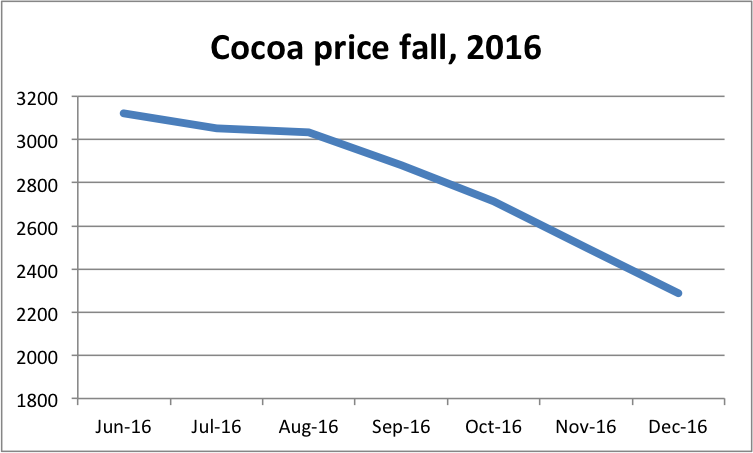

Cocoa needs rainfall to flourish. During the most recent El Niño cycle, drought conditions in Ivory Coast and Ghana meant that the world’s two largest producers were not supplying as much cocoa as usual. This shortened supply had kept cocoa’s price pretty high for several years, above $3000 per metric tonne. Cocoa’s price remained high even as world market prices for other food commodities fell (not to mention the price of oil, which lost 50% or more after 2014).

But then the El Niño cycle ended, and favorable conditions for growing cocoa returned in West Africa. Trees produced more fruit, more cocoa was loaded onto container ships in Ivory Coast and Ghana, and a surplus loomed. This newly heightened supply happened to coincide with a weaker-than-expected demand for chocolate (as measured through the proxy of cocoa grindings). These two conditions–abundant supply, low(er) demand–have only one price outcome: a fall.

By the end of 2016, cocoa’s price had lost about a third of its value. For the next year, it hovered around $2000 per metric tonne. With no immediate end in sight to the abundant supply, it was hard to predict when cocoa’s price might rise again.

But starting in January 2018, conditions changed. Though we are not in an El Niño cycle now (although we may enter one again before the end of the year), there were unusually dry conditions in West Africa for a few months. This meant we were looking once again at a potentially straightened supply scenario. As I mentioned last Friday on Bloomberg’s “What’d you miss?”, in the past few weeks there have been periods of heavy rain in Ivory Coast. We have had intermittent rainfall here in Accra, but nothing unusual or damaging. However, in Ivory Coast, far from welcoming the rains during a very dry period, there was concern that the heavy rains might have damaged the delicate cocoa flowers and baby pods, or cherelles, that are now on the trees. These flowers and cherelles will mature for the mid-season crop later this year. While much smaller than the main season crop, which is harvested from about October through March, mid-season crop volume is still large enough to impact price. The possibility of a smaller-than-anticipated mid-season crop put upward pressure on cocoa’s price.

Once again, there was a coincidence with change in demand. In the past week or so, the major processors released their grindings figures for the first quarter of 2018. Because we can’t exactly measure how much chocolate everyone in the world wants to eat, we use cocoa grindings–or the “grinding” down of cocoa beans into liquor, butter, and powder–as a proxy for chocolate demand. For decades, The Netherlands had the world’s largest capacity for grinding cocoa beans, with other countries in Europe (including Germany) also grinding large amounts. Recently, Ivory Coast has expanded its grinding capacity, so much so that now it sometimes surpasses The Netherlands for the position of world’s largest cocoa processor. Because both are processing so much cocoa and can therefore give a sense of chocolate demand, grindings figures from Europe and Ivory Coast can have an impact on cocoa’s price.

First quarter grindings in Europe were 5.5% higher than in the first quarter of 2017; grindings in Ivory Coast were 2% higher than the same period last year. North America’s grindings were actually a little lower than in the first quarter of 2017. But that weaker demand signal was not enough to counter the impact of the higher-than-expected grindings rates from Europe and Ivory Coast. Now, the supply-demand scenario had flipped from 2016: predictions of a lower supply, and a surprisingly high demand. This means that cocoa’s price rose.

Because we are not yet finished with April, the ICCO price average for this month is not available. But the daily price has continued to rise, edging above $2800 per metric tonne. Yesterday, April 24, New York futures were at $2821. This is still not as high as we saw during the most recent El Niño cycle, but it is starting to look close.

That was what I could report on Friday for “What’d You Miss?” on Bloomberg. In the few days since, the story has changed again. Last week, I was reading articles about how Ivory Coast’s rainfall was potentially damaging the mid-season cocoa crop; this week, the articles are all about how the helpful rainfall across West Africa is boosting mid-crop predictions.

In fact, the conditions are looking so favorable that Ivory Coast, at least, is fearful of another surplus and, with it, the inevitable price plunge. The Conseil du Cafe-Cacao, which regulates cocoa and coffee in Ivory Coast, announced that it will suspend its program to help cocoa farmers increase their yields (mainly by distributing high-yield seedlings). We can see from this zig-zag in the cocoa supply news that what we are really dealing with is people’s interpretations of events and subsequent predictions. No one knows whether the mid-season crop will be higher or lower than anticipated. Maybe the rain hurt the flowers; maybe the rain will prove a boon to supply. Every day we get more information and that can help to refine predictions, but the whole thing is pretty much a guessing game.

Where will the price will go from here? I wouldn’t venture a guess right now. The signals are too mixed for me to predict with confidence … although perhaps that is why I am a scholar and not a commodities trader. I like to analyze the signals, not to bet on them!

—————

Watch my segment, “What’s behind the surge in cocoa prices?” on Bloomberg’s “What’d you miss?”

Read more about cocoa’s price in my new book, Cocoa (Cambridge: Polity, 2018)